San Francisco Silent Film Festival - A Look Forward to Day 2

The second day of the San Francisco Silent Film Festival begins with Amazing Tales From the Archives I. UCLA will be in the house to talk about restorations, fragments and show clips of projects in progress. A free program, I always look forward to getting hints at what might be in the pipeline and seeing the little bits that are all that is left of films I'd dearly love to see.

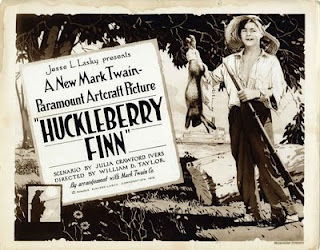

Huckleberry Finn

Accompanied By: Donald Sosin

(USA, 1920, 85 mins, 35mm)

Directed By: William Desmond Taylor

Cast: Lewis Sargent, George Reed, Gordon Griffith, Edythe Chapman, Thelma Salter

Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” is one of the most famous American novels of the 19th century. First published in 1884, the book has never been out of print. The character of Huck Finn has appeared in over 40 films starting with the 1917 version of TOM SAWYER, and was most notably played by Mickey Rooney and Eddie Hodges in THE ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN (1939 and 1960 respectively). But the first film version of HUCKLEBERRY FINN (1920), after its initial released, passed into film history and with the advent of talking pictures in the late 1920s would be forgotten and almost lost forever.

William Desmond Taylor (1872–1922) who was under contract to Famous Players-Lasky (which would later take the name of its distribution company of Paramount Pictures) had directed TOM SAWYER (1917) starring Jack Pickford and THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF TOM SAWYER (1918). So Taylor was the logical choice to direct HUCKLEBERRY FINN. Lewis Sargent as Huck started his film career only a few years before with Fox Films, in ALADDIN AND HIS WONDERFUL LAMP. An actor with a lot of presence and charm, Sargent was a perfect Huck Finn. Wanting to be as faithful to the novel as possible, Taylor went on location to Mississippi to shoot the film. Upon its release in February of 1920, HUCKLEBERRY FINN was both a critical and commercial hit.

Less than two years after finishing HUCKLEBERRY FINN, William Desmond Taylor was dead. His body was discovered lying on the floor of his living room by his butler on the morning of February 2, 1922 with a bullet wound in the back. A major investigation by the Los Angeles Police Department followed, but to this day the murder remains unsolved. Like most people who worked in silent film, his body of work is fragmentary at best. Taylor directed 64 films in the nine years he was working in Hollywood. As of this writing only 18 are known to exist.

Print courtesy of George Eastman House

***

I Was Born, But...

Accompanied By: Stephen Horne

(Japan, 1932, 90 mins, 35mm)

Directed By: Yasujiro Ozu

Cast: Tatsuo Saito, Tomio Aoki, Mitsuko Yoshikawa

There are a handful of silent, black-and-white old movies that have the power to make all the subsequent advances in the medium look redundant. When you watch, say, Charlie Chaplin’s CITY LIGHTS or THE GENERAL by Buster Keaton, you are aware of such complete mastery of the emotional and narrative possibilities of cinema that color and sound seem like so much distraction and filigree. Everything you could possibly want is here, and indeed the addition of anything else would only subtract from the perfection of the art.

I WAS BORN, BUT...” a silent feature from 1932 directed by Yasujirô Ozu, is such a movie. Ozu, who died in 1963, is best known to American cinephiles for his post-World War II dramas like TOKYO STORY and EARLY SPRING, delicate and rigorous stories of family life and generational tension in a changing Japan. The exquisite precision of Ozu’s shooting style is certainly evident in I WAS BORN, BUT... The mood, however, is comic, at times boisterously so, and the setting is a world where relations—among classes, between parents and children—seem fixed rather than fluid.

Which is not to say that there is no conflict. There is both overt and implicit violence, only some of it cushioned by the giddy energy of slapstick. And beneath the “Our Gang” schoolboy antics that make up much of the action is a clear-eyed and humane critique of inequality and authority.

The children—in particular Aoki, who was a big star in Japan at the time thanks to his appearance in Ozu’s STRAIGHTFORWARD BOY are equally adept at using broad pantomime to unlock the complexities of group relations and individual psychology. Everything in this film is utterly believable, so much so that at times it seems almost anecdotal, a sweet little anthology of kids doing the darnedest things.

That it is more—a small masterpiece, perfect in design and execution—almost goes without saying, but the film’s profundity and its charm go hand in hand. —Excerpted from the New York Times article by A.O.Scott

Print courtesy of Janus Films

***

The Great White Silence

Accompanied By: Matti Bye Ensemble

(UK, 1924, 106 mins, 35mm)

Directed By: Herbert Ponting

A hundred years ago the British Antarctic Expedition led by Captain Scott set out on its ill-fated race to the South Pole. Joining Scott on board the Terra Nova was official photographer and cinematographer Herbert Ponting, and the images that he captured have fired imaginations ever since. Ponting filmed almost every aspect of the expedition: the scientific work, life in camp and the local wildlife—including the characterful Adélie penguins. Those things he was unable to film he boldly recreated back home. Most importantly, Ponting recorded the preparations for the assault on the Pole—from the trials of the caterpillar-track sledges to clothing and cooking equipment—giving us a real sense of the challenges faced by the expedition. Ponting used his footage in various forms over the years and in 1924 he re-edited it into this remarkable feature, complete with vivid tinting and toning. The BFI National Archive—custodian of the expedition negatives—has restored the film using the latest photochemical and digital techniques and reintroduced the film's sophisticated use of color. The alien beauty of the landscape is brought dramatically to life and shows the world of the expedition in brilliant detail. A happy scene of Scott and his team in a tent demonstrating how they would cook and sleep on their race to the Pole—the same tent that would be their tomb—is particularly poignant. —Bryony Dixon and Robin Baker, BFI National Archive

Print courtesy of the British Film Institute

***

Il Fuoco

Accompanied By: Stephen Horne

(Italy, 1915, 51 mins, 35mm)

Directed By: Giovanni Pastrone

Cast: Pina Menichelli, Febo Mario

Pina Menichelli’s diva in Giovanni Pastrone’s IL FUOCO is pure, unadulterated femme fatale. Like most dive of the Italian cinema of this era, she moves sinuously and elegantly, giving herself more to the camera than to the man she seduces. But unlike many of the other dive, in this role she is untouched by fatal disease, uncanny apparitions, or even by a blemished reputation. For once, the woman is as much an artist as the man. When writing a poem inspired by the sunset, she spies a young painter (Febo Mari) who seems to come close to capturing (with her help) the right tinge of red, and proceeds to initiate her seduction. She is a practiced predator. Her owl headgear, clenched teeth, and parted lips reveal an animalistic instinct to hunt but not to devour her prey. Rather, her pleasure is to pounce on her little field mouse of a painter, toy with him, and then toss him away. After she orchestrates his creation of a masterpiece with her as its subject—a daring and kitsch nude portrait modeled on Cabanel’s “The Birth of Venus”—she will have no further use for him.

Bypassing the familiar spectacle of female suffering, but not, as might be expected, by turning to any consequent pathos for the male, IL FUOCO offers the pleasurable spectacle of a diva whose only love is herself. Menichelli’s poet takes pleasure in her own taking of pleasure. Pleasing herself despite a pronounced disdain for her pleasure’s ostensible object, she performs a very pure kind of narcissism. All her seductive movements are activated by a counterforce that simultaneously pushes away what she must nevertheless attract–if only in order to be able to throw it away and exalt in herself alone. Italian silent dive are known for their convoluted, tortuous gestures, but to watch Menichelli quickly seduce her young field mouse and then just as quickly get rid of him is to truly understand the counterforces of attraction and repulsion. In a wonderful final touch of realism, the artist notices a mole on her breast and adds it to the painting. Displeased, Menichelli’s poet rubs it out, once again “correcting” his art, perhaps because it mars the ideal beauty of her nude but perhaps also because it would make her recognizable to the public. She seeks both recognition and anonymity. In the end, the only possible tinge of regret this diva will show will be yet another gesture of narcissism: to touch this mole on her breast in memory of a passion consumed by fire. —Linda Williams, Giornate del Cinema Muto

Print courtesy of Museo Nazionale del Cinema, Torino

Individual tickets and festival passes may be purchased online at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival website.

Comments