Virginia Rappe & The Search for the Missing Juror - Guest Post

|

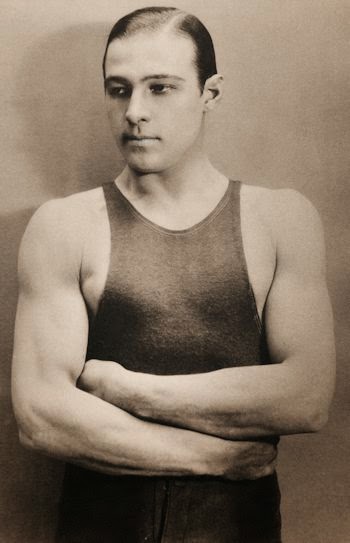

| Virginia Rappe circa 1918 |

100 years ago today actress, model, fashionista Virginia Rappe died at the age of 26 years old. For nearly the entirety of the following 100 years she would be referred to in only the nastiest of ways, whore, the slut who caused Mack Sennett to fumigate the lot because of her, alcoholic and sleazeball who got what she deserved. Finally, the person who ruined Roscoe Arbuckle's life and career. Yeah, she got what she deserved, she ended up dead, dying a horrible death. These stories that have been bandied about for decades have been disproven and one voice I remember best is that of my friend Joan Myers who was deep into researching the fracas of what was known as The Arbuckle Trial(s) and the death of Virginia Rappe. Sadly, for many reasons, Joan ultimately did not continue her research and her planned book. Her research survives and she left small trails on the internet for people to find. Back in 2009 I shared a link to a post from New Feminist Media, but, it will take you to a dead link. I reproduce below the full text of Joan's article:

The Search for the Missing Juror

by Joan Myers

In September 1921, silent film comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle was arrested in San Francisco for the murder of a woman named Virginia Rappe. The murder charge was later reduced to manslaughter, a crime for which Arbuckle was tried three times. The first two trials ended in hung juries; the third and final trial resulted in Arbuckle’s acquittal in April 1922. The Arbuckle trials became Hollywood’s first ultra-sensational “celebrity scandal.”

Arbuckle scandal canon holds that the first trial jury hung due to the malevolence of one woman juror, Mrs. Helen Hubbard. The facts are imperfectly understood and details of the story vary, but they are usually regurgitated thusly: Mrs. Hubbard believed that Arbuckle was guilty and wangled her way onto the jury intending to convict him. Mrs. Hubbard refused to review evidence or trial transcripts during deliberations. Mrs. Hubbard claimed that she would vote Arbuckle guilty until hell froze over. This woman’s obtuseness is such a cherished tenet of Arbuckle scandal belief that the first jury’s final vote is often misreported as eleven to one. But in fact, Arbuckle’s first jury hung by a vote of ten to two.

It seems we’ve mislaid a juror.

This essay reexamines the first Arbuckle trial jury vote, the legendary intransigence of Mrs. Helen Hubbard, and the mysterious disappearance of the second juror. Since jury deliberations are private and not recorded, our only sources for this story are the contemporary newspapers. Using newspapers as sources for historical analysis is problematic, but given the lack of alternatives in this case, use them we must. All sources--no matter how reliable--have limitations, but if approached cautiously both a source and its limitations can be illuminating.

We should properly locate the story within its historical context. Momentous social changes were taking place in 1921. Women, like June, were busting out all over--and not everybody was happy about it. The 19th Amendment, granting women the right to vote, was ratified by Congress on August 26, 1920. California had granted that right nine years earlier, in 1911, but a woman’s right to serve on juries remained in question. Jury composition was determined by the California Code of Civil Procedure, which defined juries as “a body of men”; debate centered upon whether the term “men” included women. Some officials took the position that the right to vote included the right to serve on juries, and accordingly women were summoned for the first time throughout California in October 1911.

By November 1921, when Arbuckle’s first trial began, none of the voiced predictions had yet materialized, but the anxiety had not abated. Media coverage of women on juries simultaneously reflected the societal concern and exacerbated it by keeping the issue on the front burner. Reporters lavished attention on the female jurors, covering age, looks, marital and economic status, attire, responses during voir dire, and votes.

Roscoe Arbuckle’s first trial began on November 14, 1921 amidst more-than-usually intense press speculation that women might be included on his jury. News reports covered the five-day jury selection process in colorful detail, emphasizing the sensational moments. And sensational moments there were. Attorneys for both sides seized every opportunity to try the case during jury selection, hurling accusations and indulging in flights of lawyerly rhetoric. Judge Harold Louderback finally halted the squabbling by ordering attorneys to select a jury and reserve the oratory for the trial.

Hubbard and Kilkenny refused press interviews and hastened from the Hall of Justice. Eager reporters converged on the remaining jurors. Either they canvassed only the women jurors or only considered the responses of the women newsworthy, because (with the lone exception of juror Arthur Crane) the next day’s reports contain quotes only from the women. The male jurors were, apparently, about as newsworthy as “dog bites man.”

It was learned from these first interviews that during the forty-four hours of deliberation, many ballots were taken and votes shifted between ballots. Hubbard, juror Louise Winterburn, and an unknown juror voted guilty on the first ballot; Kilkenny cast a blank ballot. On the second ballot Hubbard, Winterburn, and Kilkenny voted guilty, and the unknown juror changed his vote to not guilty. Kilkenny shifted his vote to not guilty on the third ballot and stayed there for the fourth; Hubbard and Winterburn voted guilty on both ballots. After discussion the fifth ballot was taken, whereupon Winterburn changed her vote to not guilty and Kilkenny changed his to guilty. From that point on Kilkenny remained unwavering and uncommunicative and there the vote remained until deliberations were halted.

Winterburn told reporters that she was conflicted: “Sometimes I think he is guilty and sometimes I believe him innocent.” Mrs. Kitty MacDonald revealed that the element of reasonable doubt played a large part in the stand of some of the jurors: “We felt that the case had not been sufficiently proved,” she said. “Some of the jurors believed that Arbuckle was innocent, others believed that not enough proof had been presented to warrant a conviction.” She told reporters that Mrs. Hubbard had expressed her belief in Arbuckle’s guilt, delineated her reasons, and would not change her vote. Mr. Kilkenny, she said, refused to discuss his vote at all. Jurors Arthur Crane and Dorothy O’Dea reported that the ten jurors who voted for acquittal tried their best to swing the two opposing votes. “We had some wild times in the jury room before it was over,” O’Dea admitted.[1]

Later that evening, Helen Hubbard broke her silence and gave a lengthy interview to a young friend, Geraldine Sartain of the San Francisco Chronicle.[2] After first expressing surprise that she had been chosen as a juror--as an attorney’s wife, she had assumed she would be challenged--she explained her vote by analyzing the testimony of the witnesses, the forensic evidence, and the legal strategy and arguments. She was unimpressed with both the defense witnesses and Arbuckle’s attorneys. “The entire case in the jury room was the trial of the District Attorney’s office rather than the trial of Arbuckle,” she said.[3]

She remained calm through the reporter’s questioning until asked about her treatment in the jury room. She then became angry. She described the behavior and comments of her male counterparts, reserving specific ire for jury foreman August Fritze, whom she accused of abusive behavior in his attempts to induce her to change her vote. Similar behavior was not, she pointed out, directed toward Mr. Kilkenny. The Hubbard interviews are detailed and they are informative. Mrs. Hubbard did not need to “review the evidence” or “read the transcripts” in the jury room because she had heard the evidence in the courtroom. She believed Arbuckle was guilty. And she was not amenable to bullying.

Thomas Kilkenny was never interviewed.

That night Arbuckle’s lead attorney, Gavin McNab, responded to Mrs. Hubbard’s comments: “I will say this about the lady juror, Mrs. Hubbard, that is, that as soon as she was sworn in as a juror the defense counsel were unanimous in the opinion that from the expression of her countenance, that whenever the defense tried to present any matter, she manifested extreme hostility and prejudice. We concluded, therefore, that regardless of the attitude of all or any one of the jurors, that she would hold for the prosecution.” With this statement, McNab places the responsibility for the hung jury solely on Mrs. Hubbard and covers his legal posterior by claiming that Mrs. Hubbard’s manifestations of “extreme hostility and prejudice” occurred only after she was sworn in. No such manifestations were discerned during voir dire by Arbuckle’s five munificently-recompensed attorneys or by the legion of reporters present in the courtroom.

McNab did not comment on Mr. Kilkenny’s manifestations.

Later that evening Arbuckle issued an official response regarding the deadlocked jury (the statement purportedly came from Roscoe Arbuckle himself; although he probably approved it, his lawyers undoubtedly wrote it). The statement opened with: “But for one woman on the jury--of twelve representative men and women--who refused to allow her fellow jurors to discuss the evidence or reason with her, and who would not give any explanation for her attitude, my trial would have resulted in an immediate acquittal.”

Mr. Kilkenny is not mentioned in this statement.

Although the December 5th papers reported the vote as ten to two, coverage then and later centered on Hubbard’s refusal to be guided--or intimidated--by her male peers. Kilkenny’s vote was soon forgotten, all the more quickly because he was intelligent enough to remain completely mum. Also ignored were the jurors who’d voted not guilty due to reasonable doubt rather than any firm belief in Arbuckle’s innocence. Mrs. Hubbard became “the woman who hung the Arbuckle jury,” and the newspapers finally had their “Man Bites Dog.”

That Arbuckle’s attorneys focused on Hubbard to the exclusion of Kilkenny, however, can only be explained as a cynical attempt to exploit public anxiety. McNab later began publicly referring to the first trial vote as eleven to one, completing Mr. Kilkenny’s rout. The ploy was as breathtaking as it was successful, and it provided the public and Arbuckle’s defense team with the archetypal story both wanted: “Woman Bites Man.”

What happens in the confines of the jury room is theoretically sacrosanct, but during my three years’ research into Roscoe Arbuckle’s life I discovered what happened that weekend in December, when the jury deliberated about Roscoe’s guilt or innocence.

|

| Joan on a day we visited Angelus Rosedale Cemetery in 2007 |

Joan Myers on "The Search for Virginia Rappe in Film History" from DJ Zoe Trop on Vimeo.

You can also enjoy a lengthy interview with Joan on Frank Thompson's excellent podcast The Commentary Track. Andre Soares also interviewed Joan at his Alternative Film Guide blog. Thanks to mine and Joan's good friend Camille who found the the new link for the article referred to in Andre's post Minta Durfee and the Last of the Terrible Men. In fact, here is a link to the article I posted above, the Minta Durfee article and the video from the new website from Vicki Callahan.

While all of Joan's friends are sad that she ultimately decided to not continue with her manuscript, the good news is that Joan's research does survive and there are plans to utilize it, it is just not going to happen today. As soon as I know more, I will certainly share it.

Comments